One of rock's most beloved and contrarian figures has died. Lou Reed epitomized New York City's artistic underbelly in the 1970s, with his songs about hookers and junkies. He was 71.

Reed died Sunday morning on Long Island of complications from a liver transplant earlier this year, his literary agent, Andrew Wylie, said.

The famous iconoclast actually got his start as a staff songwriter pumping out pop tunes in a wannabe hit factory called Pickwick Records. Reed recalled his days as a frothy pop lyricist in a 1989 NPR interview.

"When I first started out I really liked the spontaneity of it, cause you know I've got a B.A. in English — not that that means I should be good at it, but it gives me some kind of background in it," he said. "I thought I was pretty fast."

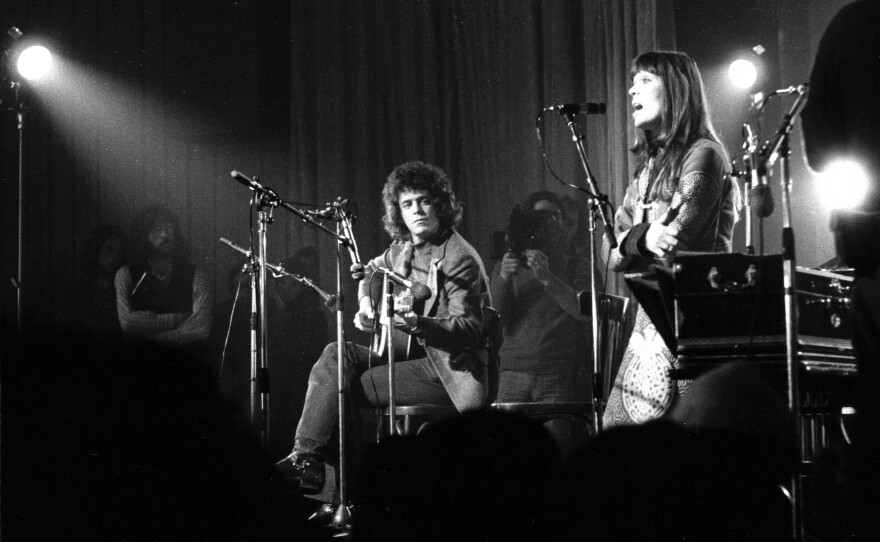

Lou Reed was fast. In more ways than one. He went from hit factory to Andy Warhol's Factory, the epicenter of trashy, avant-garde experimentation in '60s New York. Warhol mentored Reed and his band, The Velvet Underground. He urged them to keep things gritty. The band's Welsh co-founder, John Cale, told NPR in 2000 that the band was never easy listening.

"We were not user-friendly at all," he says. "Anyone listening to a bass guitar and regular guitar coming out of the same amp — it couldn't have been a really great listening experience."

Beyond their sound, The Velvet Underground disturbed even hard-core scenesters with graphic songs about debauchery and doing drugs. In an interview on WHYY's Fresh Air, drummer Moe Tucker remembered performing the song "Heroin": "We got fired from the Cafe Bizarre," she said. "The woman came rushing up to us and said, 'If you play one more song like that you're fired.' "

They did, and they were, and the band's albums did not sell very well. Reed left and embarked on a spotty solo career that reflected his up and down life enthralled with New York's darker corners and the hustlers who hid there.

"Walk on the Wild Side" became Reed's only Top 40 hit, partly because a number of radio station programmers had no idea what it was really about. The album it came from, Transformer -- co-produced by David Bowie — brought Reed critical acclaim and attention. Which Reed, in characteristic fashion, hated. That played out in interviews, including one in 1989 with NPR's Bob Edwards, who asked Reed about his choice of subjects.

"I mean, it might be harder to write about a chair," he said. "As a matter of fact, it would be harder to write about a chair. I mean, I could write a song about a chair: Who sat in this chair. Who built this chair. How long had this chair been here. You could do that."

And a few years later, while promoting his album The Raven, Reed vented to another NPR host, who wanted to know how other journalists had somehow mixed up Reed's original lyrics with the writings of Edgar Allan Poe.

"Well, if you're deaf, dumb and retarded, it's easy. I can't believe people interview me for this stuff and don't notice," he says. "I grade them and I put them on my website when they fail really badly, to warn other people, other musicians: 'Watch out for this interviewer.' It's like talking to a squirrel."

As ornery as Reed was with journalists, he was often supportive of other artists. He influenced REM, The Replacements and Talking Heads, and he collaborated with musicians ranging from Metallica to a young woman he met at a concert.

"I just said, 'Hey, hey Lou Reed. This is Emily Haines.' " Haines talked to NPR in 2012 about her band, Metric. She said Reed asked her if she would rather be in The Beatles or The Rolling Stones. She said The Velvet Underground. Then she asked if he would sing on her album. "I just asked him, and he said, 'Yes.' "

When Reed was not onstage or working with other artists, he was happiest in New York City, where he mellowed into a Lower Manhattan elder statesman, riding his bike, practicing tai chi and taking photos. He could get cranky about his own composition.

"I did not place that stupid bird there," he said in an interview he gave Weekend Edition in 2006, walking around his neighborhood with his camera. "The light comes and goes so quickly when it's perfect. You know that. There's a certain time in the morning, certain time around dusk, where the light is golden."

An ephemeral moment, like Warhol's Factory. Or a city sunset. "And I wanted to catch that," he said. Lou Reed caught it — on celluloid and vinyl.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.